El paisaje más grande: La Red de Agricultura estadounidense

Thomas Jefferson diseñó la mayoría de América ... y no estamos hablando de que el gobierno federal o incluso Monticello .

Si alguna vez has volado por las llanuras de América del Norte esto es lo que has visto: interminables kilómetros de formas cuadradas y circulares, todas llenas de matices terrosos. El campo se extiende implacable de horizonte a horizonte, y puede ser aterrador si no fuera por la vegetación puntillista que lo convierten en un extraña pintura paisajística. Pero ¿por qué círculos y cuadrados ? ¿Cómo podía medio continente estar cubierto en un solo diseño hiper - riguroso ? Es gracias a una extraña interacción de diseño y tecnología que abarca a más de 200 años, hasta el final a Thomas Jefferson.

Thomas Jefferson diseñó la mayoría de América ... y no estamos hablando de que el gobierno federal o incluso Monticello .

Si alguna vez has volado por las llanuras de América del Norte esto es lo que has visto: interminables kilómetros de formas cuadradas y circulares, todas llenas de matices terrosos. El campo se extiende implacable de horizonte a horizonte, y puede ser aterrador si no fuera por la vegetación puntillista que lo convierten en un extraña pintura paisajística. Pero ¿por qué círculos y cuadrados ? ¿Cómo podía medio continente estar cubierto en un solo diseño hiper - riguroso ? Es gracias a una extraña interacción de diseño y tecnología que abarca a más de 200 años, hasta el final a Thomas Jefferson.

Campos de cultivo circulares en Kansas, EE.UU. Imagen : NASA a través de wikipedia.org

¿Y cómo Jefferson, político, académico, y arquitecto, logró diseñar la extensión del oeste de Estados Unidos ? Mucho antes de que existiera el Gobierno Federal , el Congreso Continental en 1784-1785 estaba lidiando con la forma de organizar la futura resolución en la frontera. A los 41 años de edad, Jefferson ayudó a redactar y aprobar ordenanzas que ambiciosamente se repartieran el West utilizando esa herramienta favorita de Jefferson y su arquitecto ídolo Palladio: la red .

Así como Palladio utiliza una cuadrícula para organizar sus edificios , Jefferson

utilizaría el sistema racional para diseñar el plan del joven país, literalmente, hasta el último

bloque.

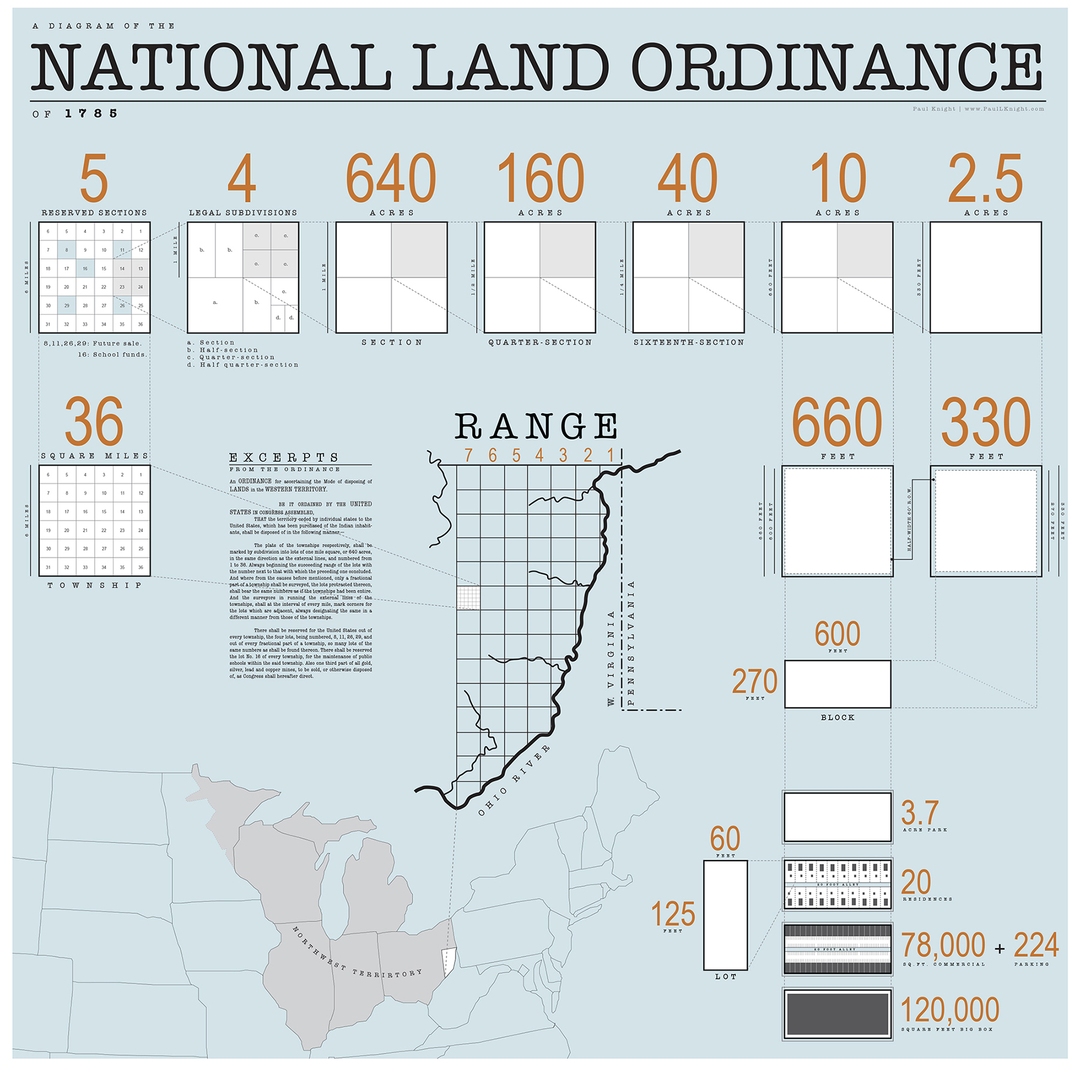

La Ordenanza de Tierras de 1785 que serviría como base para el Sistema de Catastro Público. Imagen: Isomorphism3000 través wikipedia.org

Sin embargo , no se trataba de un plan megalómano o incluso de una obsesiva precisión. El sistema que ayudó a formular se basa lógicamente en algunas convenciones de encuestas existentes, pero Jefferson no podría haber ayudado, sino viendo que no se trataba sólo de las líneas de propiedad. Para él, se trataba de la elaboración de una nación democrática de los ciudadanos agrarios: "hacendado " . La red se extendería por las llanuras fértiles de diversas escalas ( 24 x 24 mi patio , 6 x 6 mi municipio, sección 1 x 1 km ) , pero siempre culminaría en un x 1/ 16 mi 1/16 ( 40 acres ), terreno ideal para una casa unifamiliar. No eran sólo líneas en un mapa, sino una forma de diseñar el futuro de la forma de vida americana según Jefferson.

Indiana tierras de cultivo. Imagen: Paul Knight a través de thegreatamericangrid.com

Indiana tierras de cultivo. Imagen: Paul Knight a través de thegreatamericangrid.com

Por supuesto, los Estados Unidos no mantienen una nación de agricultores , y las líneas que la red establecia se convirtió en la base para los pueblos y ciudades de todo el Medio Oeste. En el giro final , la mayoría de los agricultores ( y ahora las empresas agrícolas ) usan riego de pivote central , que produce esos círculos icónicos de crecimiento. A pesar de que el extraño paisaje no es exactamente como Jefferson imaginó , la naturaleza definitivamente democrática de la red significa que sus propiedades privadas son libres de desarrollar sus parcelas a su antojo. Su diseño era más resistente de lo que se haya imaginado, y Jefferson, donde quiera que sea, no estará muy infeliz.

Estados Unidos no es el único país que ha usado riego de pivote central . Las tierras agrícolas en el desierto de Arabia Saudita , 2012 . Imagen: earthobservatory.nasa.gov

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

ENGLISH VERSION

Largest Landscape: The Grid Of

American Agriculture

Thomas Jefferson designed most of America... and we're not talking about the federal government or even Monticello.

If you've ever flown across the North American plains you've probably seen it: endless miles of square and circular shapes, all filled with earthy hues. The relentless gridiron stretching from horizon to horizon might be frightening if not for the pointillist greenery making some strange landscape painting. But why circles and squares? How could half a continent be covered in a single hyper-rigorous design? It's thanks to a strange interplay of design and technology that spans back more than 200 years, all the way to Thomas Jefferson.

Circular crop fields in Kansas, U.S.A. Image: NASA via wikipedia.org

And how did Jefferson, a politician, scholar, and architect, manage to design the expanse of the American West? Well before the Federal Government even existed, the Continental Congress in 1784-1785 was grappling with how to organize future settlement on the frontier. The 41-year-old Jefferson helped write and pass ordinances that would ambitiously carve up the West using that favorite tool of Jefferson and his architect idol Palladio: the grid. Just as Palladio used a grid to organize his buildings, so Jefferson would use the rational system to lay out the plan of the young country, literally down to every block.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 that would serve as the basis of the Public Land Survey System. Image: Isomorphism3000 via wikipedia.org

However, this wasn't about megalomaniacal planning or even obsessive precision. The system he helped formulate was understandably based on some existing survey conventions, but Jefferson couldn't have helped but see that it wasn't just about property lines. For him it was about crafting a democratic nation of agrarian "yeoman" citizens. The grid would extend over the fertile plains in various scales (24 x 24 mi quadrangle, 6 x 6 mi township, 1 x 1 mi section), but it would always culminate in a 1/16 x 1/16 mi (40 acre) plot, ideal for a single-family homestead. These weren't just lines on a map but Jefferson's way of designing the entire future of the American way of life.

Of course, the United States didn't remain a nation of farmers, and the lines that the grid established became the basis for towns and cities across the Midwest. In the final twist, most farmers (and now farming corporations) use center pivot irrigation, which produces those iconic circles of growth. Even though the strange landscape isn't exactly how Jefferson imagined it, the grid's definitively democratic nature means its individual owners are free to develop their plots as they please. His design was more resilient than he may have realized, and Jefferson, wherever he may be, can't be too unhappy.

America isn't the only country to use center pivot irrigation. Farmland in the Saudi Arabian desert, 2012. Image: earthobservatory.nasa.gov

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario